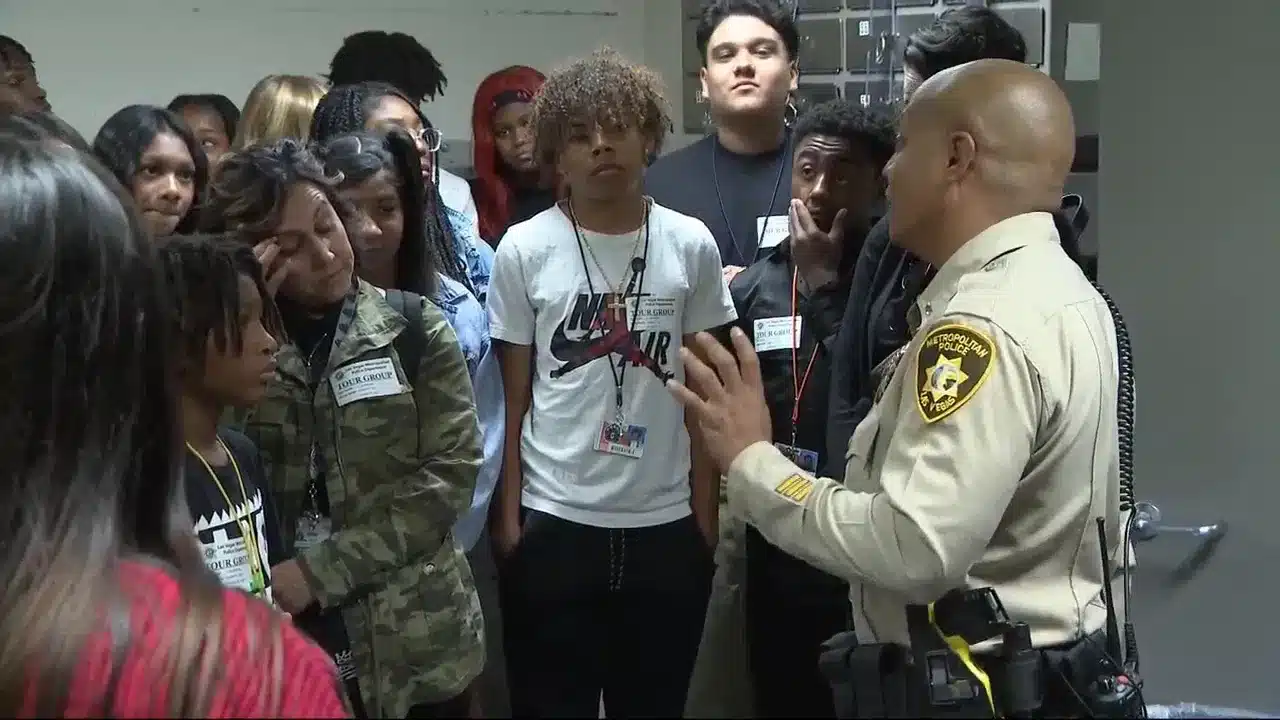

LAS VEGAS (KSNV) — Lt. Joey Quidachay is used to managing large groups inside the Clark County Detention Center.

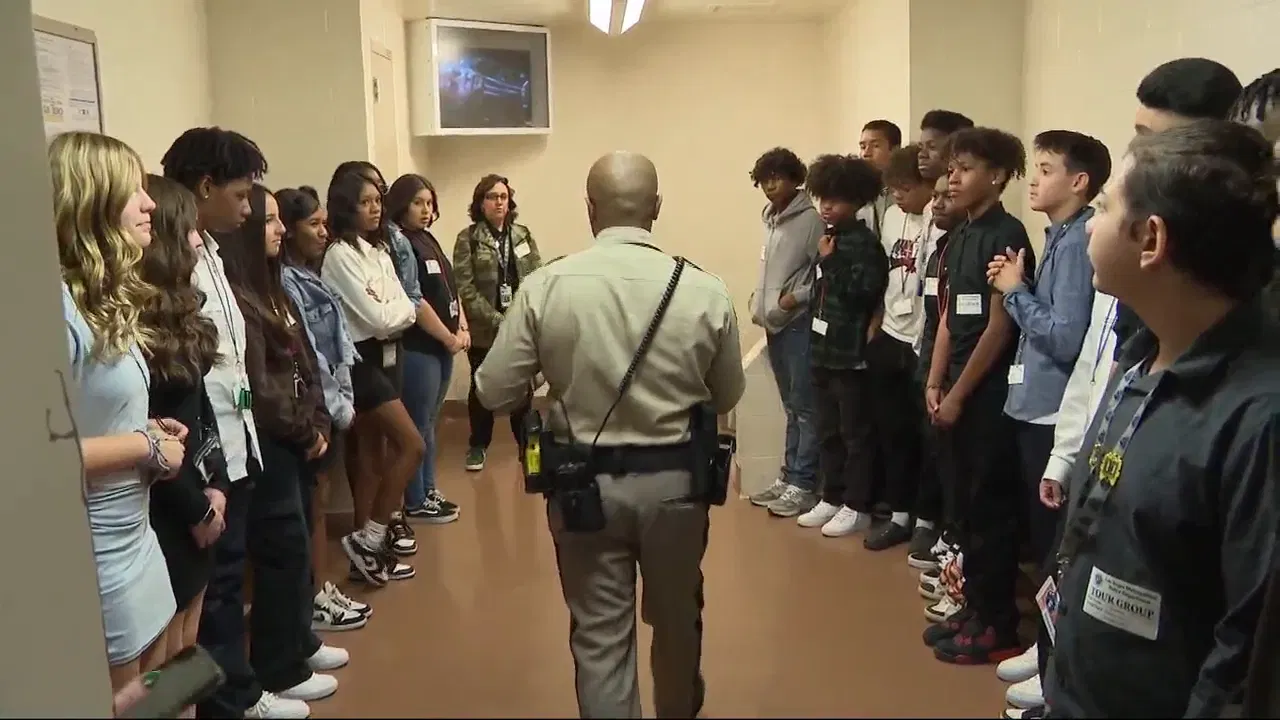

“When we cross this threshold there is no more joking,” he says. “When you get in this elevator you will not talk, three across facing the rear.”

But not quite like this.

On Thursday, two dozen students from Gunderson Middle School were given a tour of what life behind bars can look like.

“There’s a distinct noise when that door shuts that’s the last thing you hear,” says Quidachay.

The students are part of LEEAP, Law Enforcement Empowerment and Athletic Program.

Metro police providing mentoring inside 13 local schools.

This is the first time they’ve left campus for a field trip.

“It’s not D.A.R.E. it’s not a Scared Straight program. It’s not we’re the big bad police and you need to do what we say,” says Sgt. Matt Kovacich. “It’s more of a positive interaction where you can speak with the kids, see what’s troubling them.”

The program is one solution to a growing societal problem of young teens finding themselves charged with adult crimes.

A recent example is 18-year-old Jesus Ayala and Jzamir Keys who are accused of murdering a local bicyclist.

Jon Ponder with the nonprofit Hope For Prisoners says good decisions begin with the people you choose as friends.

“If you talk to the men and women who are incarcerated right now that’s what the trend is,” he says. “They started doing things when they were 12,13,14 years old and it spiraled out of control from there.”

Just ask Graham Miller.

An ex-felon who tells the kids his biggest mistake was not listening to his mother and grandmother.

“It’s all because of the people I associated myself with. My home boys, my home girls,” says Graham. “I spent most of my juvenile life locked up. In and out. My mom would tell you that was my second home.”

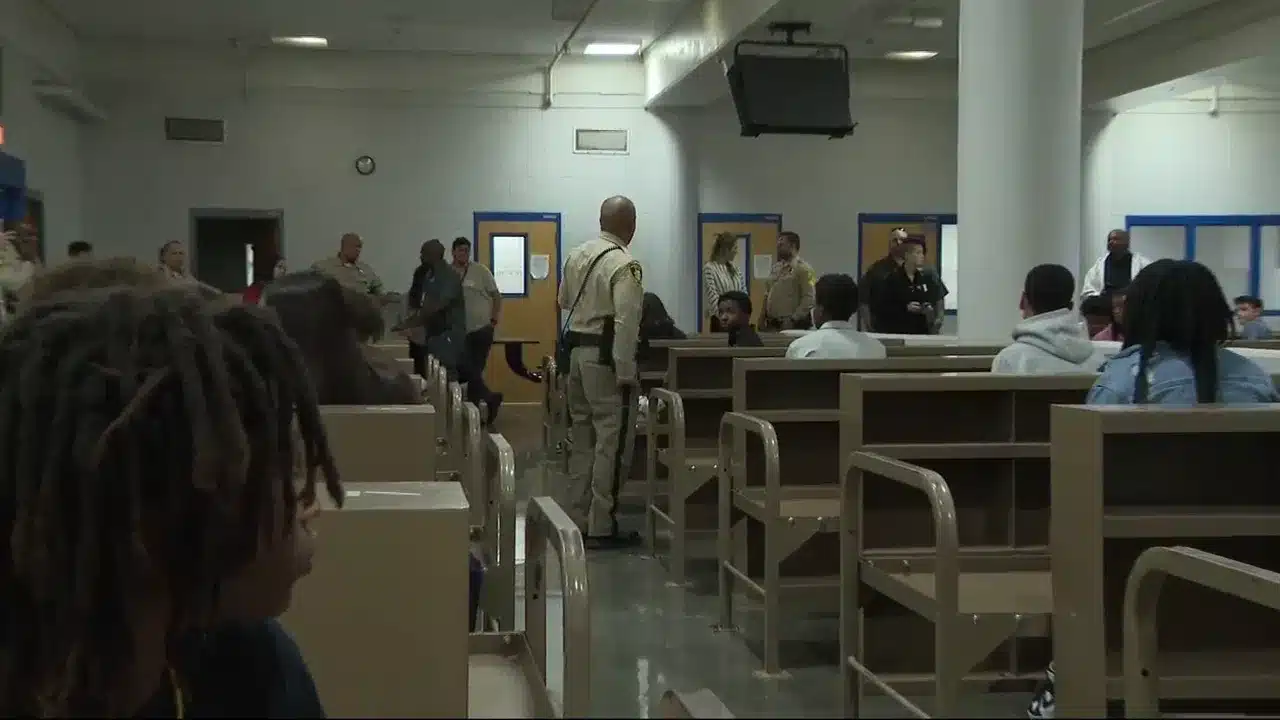

Back on the tour students are shown a holding cell where the water fountain and toilet are one and the same.

One young man was seen cringing at the sound of a flush.

“You’re doing everything in here right?” says Lt. Quidachay.

Want toilet paper? Quidachay says you’ll need to ask the biggest guy in the cell who’s probably using it as a pillow.

“Those are unwritten rules,” he explains. “Don’t have to worry about those rules if you stay out of this place.”

Eighth graders Janiya Pinkard and Keegan Besser promise they will.

“At first I was like what did I set myself up for you know what I mean?” says Pinkard. “But I had a really good time seeing what I don’t want to do with my life.”

“It’s not what people would expect,” adds Besser. “You think it’s like the movies, it is not. Walking in there it was so nerve-wracking.”

And one major takeaway for the students is the complete lack of privacy.

Seventy-four inmates per dorm.

Constantly told what do to, and when to do it.

“At 10:59 every night you’re going to read, write, or sleep,” says Quidachay. “Those are your only options, no looking at your phones.”

Call it a dose of reality.

Seeing what can happen when actions have consequences.